AUGUSTA, Ga. — At about 10:55 a.m. the crowd parted all on its own. No security told people to do it. No ropes were pulled out. Nothing was imminent. This was in front of the famed Augusta National clubhouse, under the sprawling live oaks that offer scenery and shade, some of the most exclusive ground in this exclusive country club.

Tiger Woods was coming. He wasn’t there yet, but he was coming. Everyone knew that. He was set to tee off at 11:04 which meant he would be emerging from the clubhouse for a walk that seemed nearly impossible 14 months ago when he rolled his SUV over a Southern California median, across two lanes of road, through a wooden sign, off a tree and finally into a ditch.

Both his right tibia and right fibula busted apart and right through the skin. Tiger was so dazed, he told a sheriff’s deputy he was in Florida. Initial onlookers feared death. Doctors considered amputation. Woods would spend nearly a month in the hospital and then three more at home, bedridden because he was neither strong enough nor healthy enough to get up “even to see my living room.”

Now he would soon be emerging, a golfing sensation turned near ghost turned modern medical miracle.

Tiger Woods, Tiger damn Woods, was going to return to golf, going to defy the odds, was going to play the Masters.

Impossible 14 months ago. Improbable 14 days ago. Yet now upon us and, inexplicably, among the leaders at 1-under, four off the lead.

So yeah, they were going to clear a path even before anyone told them too. These weren’t the regular fans with regular tickets who were packed 40 deep around the tee box. No, these were the elite of America’s elite lining up. An internet billionaire. The greatest female golfer of all time. A primary owner of Pebble Beach. An oil magnate. The commissioner of the NFL.

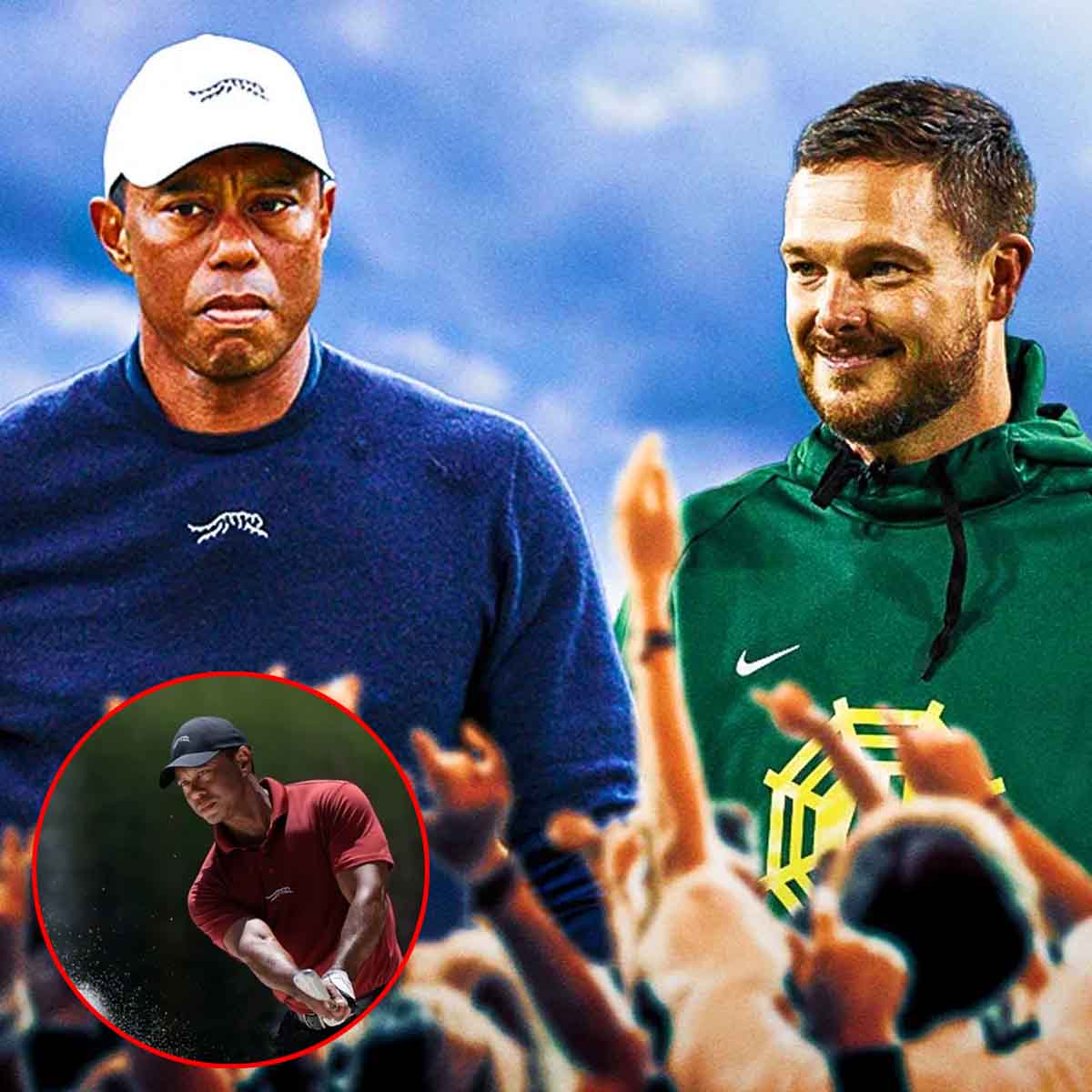

The group of Tiger Woods, Joaquin Niemann of Chile and Louis Oosthuizen walks off the first tee during the first round of the Masters on Thursday. (Photo by Jamie Squire/Getty Images) (Jamie Squire via Getty Images)

And they stood and waited until Tiger Woods emerged, clad in pink, muscles bursting, no sign of hobble in his step. He confidently and steely eyed walked down their makeshift lane, cheers on all sides clueing in the masses by the first tee that their guy was coming, their hero was back.

Maybe it was that you can’t truly appreciate something until it’s (seemingly) gone, or maybe it was nostalgia, or maybe how seeing a star of yesterday still playing today can make everyone feel young. Perhaps it was bearing witness to the final hurdle of a relentless rehabilitation process.

Or maybe it’s just that it was Tiger Woods, who has always brought indescribable force, fashion and fame to a sport that desperately needs it.

Whatever it was, Augusta National lost itself Thursday morning, in the promise of a future that wasn’t expected, in visions of triumphs long past. Woods has won 82 times on the PGA Tour on courses all over the globe, but Augusta has always felt like home.

It was here, in 1997, he shot 18-under to win his first major. He hugged his father and sent the sport off its axis. For a while, golf tried to resist. Even here at Augusta. They once boasted of “Tiger-proofing” the place but in the end he changed them, not the other way around.

This scene, both among the green jackets, or out with the patrons, would have been unrecognizable a quarter century ago. More people of color. More women. Some, and at a clip increasing annually, even part of the membership.

“We are a better club,” chairman Fred Ridley said this week of the decision to admit women as members a decade ago. “We are a better organization.”

What was once a venerable venue draped in stuffy traditions and almost exclusively Southern drawls is now an adult Disneyland, still gripping to the parts that made it special, but surrounded by fresh construction, sprawling parking grounds, luxury hospitality areas, a gift shop the size of a WalMart, a driving range out of your dreams.

The tournament is bigger. The club is bigger. The jets are bigger. Yet the culture is somehow more approachable, less divided, more encouraging. Dude Perfect filmed a video here recently. Hootie Johnson might have fainted.

Tiger put the National in Augusta.

The last time he played here in front of full crowds, he won the event for a fifth time, his 2019 storybook triumph punctuated by hugging his son, Charlie, on nearly the same patch of grass as he once embraced his own father, Earl. That he made it back from innumerable knee and back injuries to win at age 43, was considered an all-timer of a comeback story.

The celebration around the 18th green — with workers leaving their posts and fans hugging and crying — was perhaps the loudest this place had ever been.

The thing with Tiger, both good and bad and tabloid, is there is never a peak. Never a bottom either. There is always more. So what was once knee surgeries, spinal fusions, a roadside arrest and personal scandals is now a near-death accident.

He is a man of so much victory, yet so often winds up beaten up and broken down. Maybe that’s part of the appeal. There is a human element to a sporting myth. This was just the latest. He could never return, except, of course he would, sooner than ever.

And so they — 10,000 strong maybe packing the entire first hole — cheered and smiled and shouted his name, which he barely acknowledged across a face of intensity. He is here to win, he said. It is an outlandish goal — he’s played no competitive golf since November of 2020 – but he knows no other way. To his fans, the pending scoreboard meant almost nothing.

They stood because they didn’t know if he’d ever stand again. They strained their necks because they never knew if they’d see him swing again. They came because he came back, Tiger Woods back among the Georgia pines, back at Augusta, back walking through a tunnel of fame and fortune and among his people, back at his place.

“Now driving,” they announced. “Tiger Woods.”