There is a romanticism to the U.S. Open, a beauty that is found in its name. Open. The sport beats its chest about meritocracy, but this tournament is meritocracy incarnate. The U.S. Open doesn’t care who you are or what you’ve done, where you play or where you’re from. Its invitations are not given; they are earned.

You see, there, in the fine print of the U.S. Open entry form, Category F-23 among the exemptions from Local and Final Qualifying, the USGA notes that it reserves the right to select a player for a special exemption into the national championship. It’s a rarely used provision that dates back 58 years, one that will be given for just the 35th time next week at Pinehurst No. 2 so that one of the most decorated golfers in USGA history has a chance to compete once more.

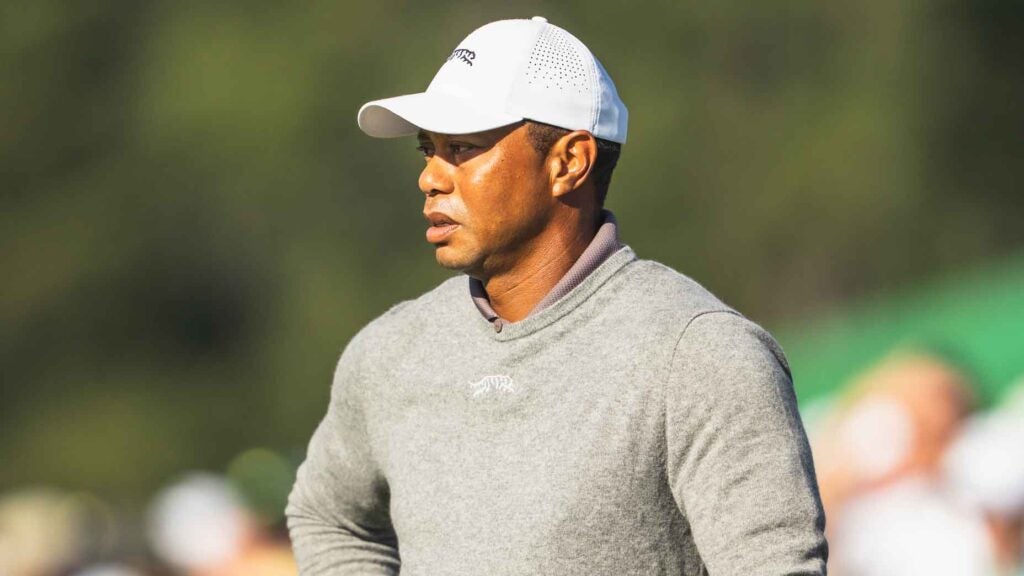

Of course, you could argue Tiger Woods has earned the special exemption by virtue of his 15 career major titles, including three U.S. Open victories. Woods has lifetime exemptions into the Masters and PGA Championship as a past champion and can play in the Open Championship until 2036, when he is 60 and last exempt thanks to his three claret jug victories. But winning the U.S. Open only comes with a 10-year exemption. With his last triumph at this tournament coming in 2008, and his five-year exemption from winning the 2019 Masters having run out, 2024 marked the first time in Woods’ professional career that he was not fully exempt into the U.S. Open.

In 2024, for the first time as a professional, Tiger Woods wasn’t already exempt into the U.S. Open.

Andrew Redington

“The U.S. Open, our national championship, is a truly special event for our game and one that has helped define my career,” said Woods, who will also receive the Bob Jones Award, the USGA’s highest honor, next week at Pinehurst. “I’m honored to receive this exemption and could not be more excited for the opportunity to compete in this year’s U.S. Open, especially at Pinehurst, a venue that means so much to the game.”

The special exemption practice began in 1966, when four-time U.S. Open winner Ben Hogan received an invite to play at that year’s championship at The Olympic Club—site of his playoff defeat to Jack Fleck in 1955. The then 53-year-old Hogan showed the invite was more than ceremonial, shooting a four-day total of 291 to finish in 12th. The special exemption wasn’t used for another 11 years until 1977, when three players (Sam Snead, Tommy Bolt and Julius Boros) were granted it.

Here’s the complete list of everyone who has gotten a special exemption from the USGA into the U.S. Open, and how they fared.

While only 35 players have been let in via special exemption, many have been gifted it multiple times. Jack Nicklaus, a four-time U.S. Open winner and two-time U.S. Amateur champ, was awarded a special exemption in eight instances, beginning in 1991 and ending in 2000. Arnold Palmer and Tom Watson both received five special invitations, with Seve Ballesteros, Gary Player, Lee Trevino and Hale Irwin also getting multiple special grants.

Irwin’s 1990 special exemption, is, well, especially special. Irwin had not won on the PGA Tour in five years, and it had been 11 years since Irwin captured his second U.S. Open title. But at age 45 Irwin shot a eight-under 280 to tie Mike Donald and proceeded to beat Donald the next day in an 18-hole playoff for his third national championship crown.

It’s not just former winners who get the special exemption. Both Aaron Baddeley and Michael Campbell received special exemptions thanks to international performances (Baddeley winning the 1999 Australian Open as an amateur; Campbell grabbing five global victories). Phil Mickelson has famously never won the U.S. Open, finishing runner-up six times. He once said that he would not accept a special exemption if it was given, but Mickelson softened that stance for the 2021 U.S. Open in his hometown of San Diego (although it’s worth noting Mickelson ultimately qualified thanks to winning the 2021 PGA Championship just weeks before).

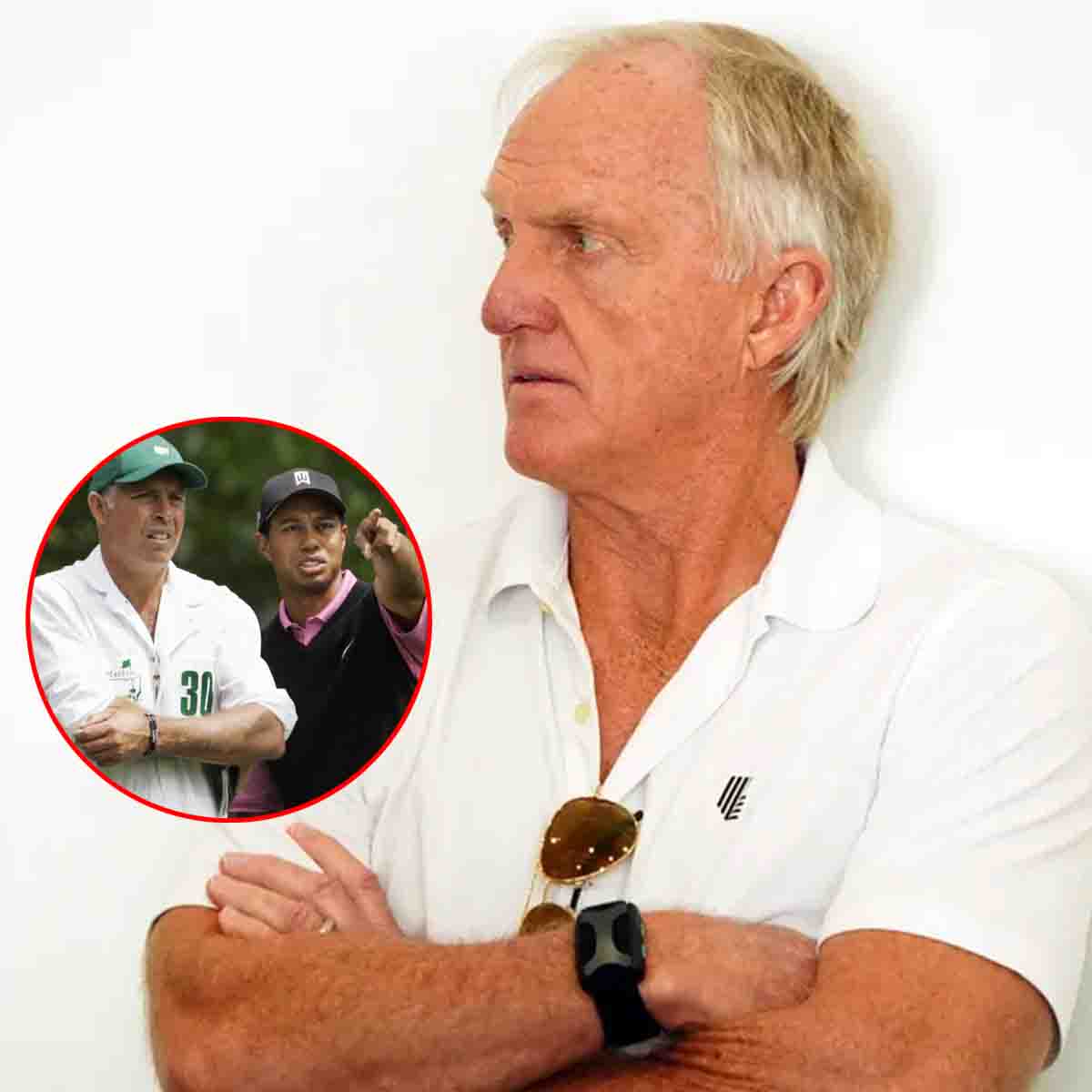

So what does this mean for Woods? No need to regurgitate all of his career accolades, but it’s worth remembering he’s played an indelible part in the USGA’s championship history, winning three U.S. Opens, three U.S. Amateurs and three U.S. Juniors to tie Bobby Jones for the most USGA titles overall. There’s also the business aspect of Woods: He continues to be the biggest draw in the sport, and U.S. Opens with Woods in the field have a higher likelihood of attracting more attention—both on the course and on television/streaming.

So it is that Woods is likely to receive more special exemptions, if needed, in the future. He most certainly will get an invite next year at Oakmont to coincide with the U.S. Open’s 125th playing. Pebble Beach, site of Woods’ historic 2000 U.S. Open win, will host again in 2027, and it’s a good bet Woods will get the nod when the U.S. Open comes to his hometown of Los Angeles in 2031. Given the USGA’s track record with Nicklaus and Palmer, the odds are high that Woods will get invites in the interstitial years should he want them.

In short, don’t be surprised if Woods’ special exemption becomes something of a trend for the foreseeable future. Or at least until Woods decides he’s no longer “earned” them.