While it’s almost impossible to imagine a world today without photos, living in the 19th century meant discovering this new technology for the first time in history. A new exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, entitled Paper Promises: Early American Photography, looks back at the influence of early photography in the United States and the many ways in which it shaped the country that we know today.

BuzzFeed News spoke with Mazie Harris, Assistant Curator of Photographs at the J. Paul Getty Museum, about the research involved in organizing the exhibition and how Americans during the 19th century made use of this new technology:

The exhibit brings together early paper photographs from the 1850s and 1860s. It was a tumultuous time in the United States, and all sorts of people — entrepreneurs, scientists, news and book editors, celebrities, families, students, lawyers, politicians, land speculators — were trying to figure out how best to make use of photography, which was still a relatively new technology at the time.

Photography was introduced in 1839, so by the 1850s, most Americans would have seen or would own a daguerreotype — one of those one-of-a-kind photos on metal. They were housed in pretty cases and came in a range of handheld sizes. They were perfect for intimate viewing, much as you might today cradle your phone in your hand while scrolling through photos online. There is that same rush of immediacy when you hold a daguerreotype today.

Paper photographs, which were initially made from paper negatives and then from glass negatives, could be printed in multiple in a variety of sizes, and could be easily mailed or tucked into an album. But they were (and still are!) more light sensitive, and didn’t have the heft of encased daguerreotype pictures.

Americans were really into one-of-a-kind photographs. These days we tend to think of ease of reproduction and sharing as key aspects of photography, but Americans really went in for daguerreotypes — which were unique and were made by direct exposure onto a metal plate without an intervening negative. Yet the idea to use negatives to produce paper photographs in multiple was known in the US fairly early on. So I became interested in trying to understand why paper photography didn’t initially take off here, as it had in Europe, despite what would seem to be the obvious advantages of the potential for duplication.

But by the time of the American Civil War, paper photographs overtook unique photographs in popularity. As families became dispersed through migration and mounting militarization, paper photos became an efficient way to share mementos and images of important people and places.

In the April 1, 1861, issue of the American Journal of Photography, an article stated, “There are few families now that have not their gallery of photographic miniatures or portraits and as few children escape the photographist’s rooms as escape the measles, whooping-cough, or kindred diseases. Indeed photography is as contagious as the small-pox.” That sort of language feels so familiar as we think about how rampant photo-sharing through social media is today!

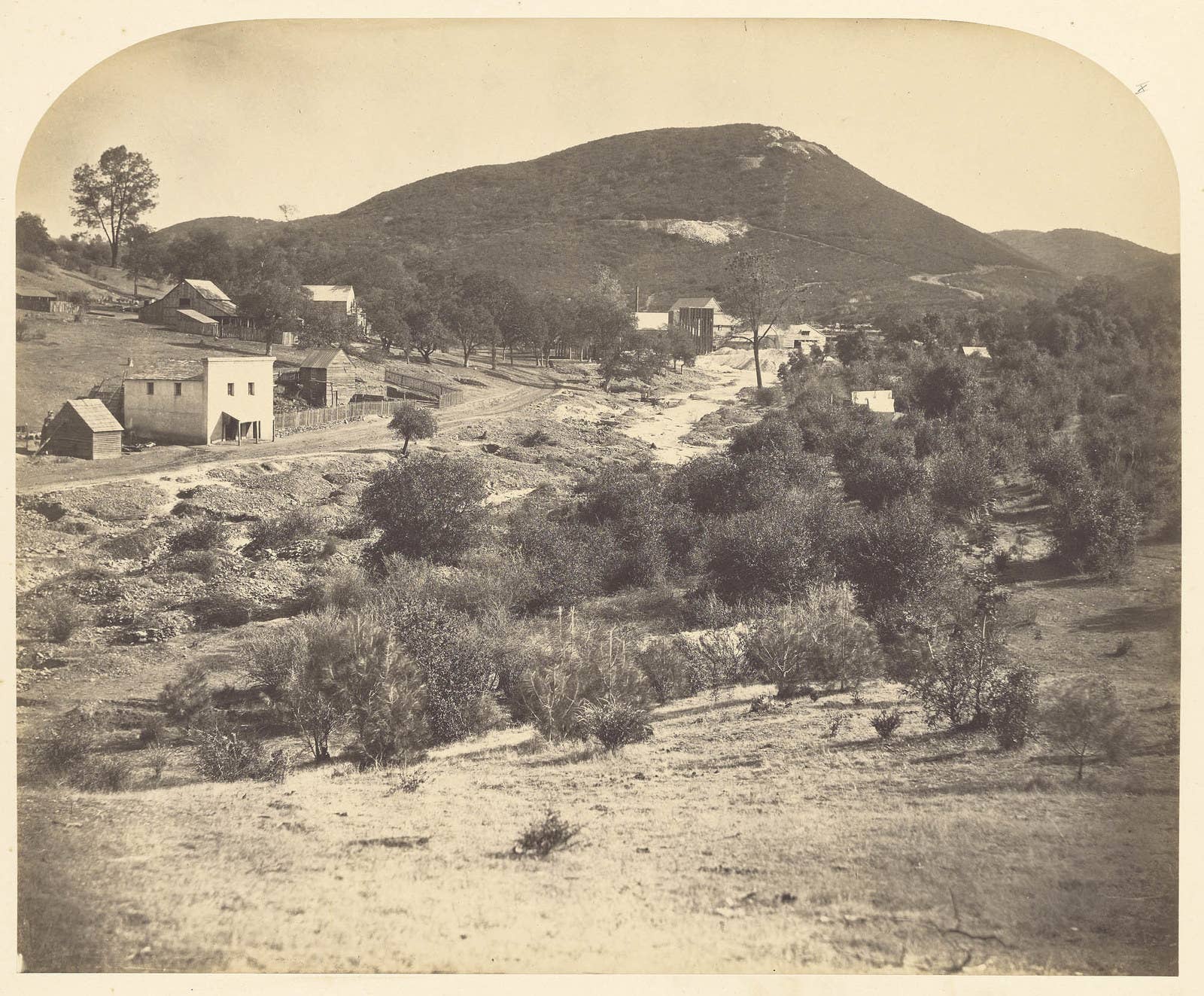

Paper photographs increasingly began to be made in large numbers and in large sizes. There are several big beautiful landscapes in the exhibition and a wonderfully intricate photographic map used during the Civil War.

One of the most popular types of paper photographs in the 1860s was quite small and referred to as the “carte de visite” format. Cartes de visite are baseball card–sized portraits that people shared and collated in albums. It was fairly common to have collections of images of celebrities and loved ones gathered together in what were basically books of faces. Friends and family would often inscribe the portraits with warm sentiments or quotations.

In the Aug. 15, 1862, issue of the American Journal of Photography, a writer marveled: “The ease with which photographs are taken, and the cheapness at which they are sold, has reached its highest development in the carte de visite. A man can now have his likeness taken for a dime, and for three cents more, he can send it across plains, mountains, and rivers, over thousands of miles to his distant friends.”

Photographs didn’t just illustrate what was happening in the world — they profoundly influenced people’s ideas and actions. Photos pretty quickly began to be used as propaganda: to encourage tourism, burnish the reputation of a celebrity, bolster support for a politician, proffer a flattering portrait of a loved one, give a favorable impression of land available for an investment deal, or to encourage Americans and recent immigrants to move deeper into the country to settle in a faraway town. The early years of photography were formative for establishing many of the ways we wield photographs today.

In mid-19th-century America, there was a great deal of enthusiasm about paper photography when it was first introduced, but also a lot of anxiety about what sorts of problems it might cause. I’m reminded of that each time we’re faced with what seems to be a revolutionary new technology these days. There’s usually a rush of coverage about what it might make possible, but also often hand-wringing about potential dangers or side effects. I was eager to learn more about how that played out in the early years of photography in the United States. Plus it’s fun to imagine how exciting it must have been to see or share a photograph for the first time!

Another fascinating part of this history are counterfeits — the photographic counterfeits I tracked down are incredibly rare and hint at one of the most intriguing aspects of the era. By the time photography was introduced into the world, America had moved away from a system of national currency and instead each bank printed its own paper bills. Imagine if every bank in your town and across the United States circulated its own form of paper currency! It was wild.

There were thousands of different bank bills in circulation, so forgeries became prolific. As a result, coins held their value more consistently then paper money, and bank bills were often referred to as no more than flimsy “paper promises.” Paper photography got wrapped up in the issue because there were widespread reports that photographic negatives were being used to produce fake bills.

At that time paper money was printed only in black ink and bills were only one-sided, so the development of “greenbacks” — bills that were two-sided and incorporated color — was prompted by the fear of photographic counterfeiting. I’d read all about that but hadn’t found any examples of photographic counterfeits, so was totally thrilled when a scholar helped me to find the examples that I included in the exhibition and book.

Those photographic forgeries inspired the title of project. It’s incredible that in the 1850s paper photography was linked to that derogatory phrase “paper promises,” yet within a decade paper photographs became one of the most prominent agents in perpetuating the promise of American progress.

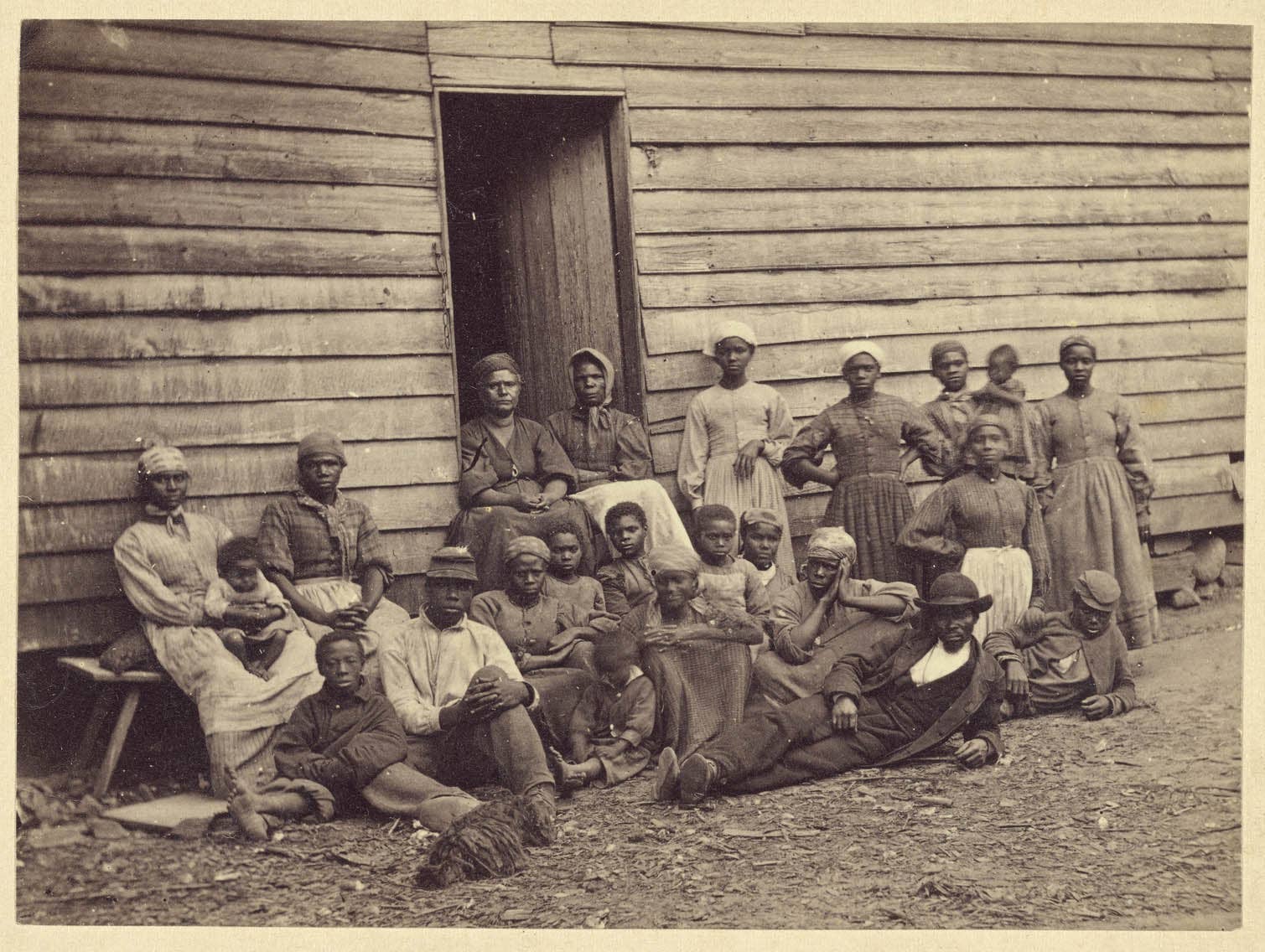

For me, working on this exhibition offers constant reminders of the long history of racial and class tensions in the United States. It’s heartening to see how photographs are being used to push for social justice today, but of course photography is also still being exploited to further restrictive ideas about America and Americans.

I hope looking at the early years of American photography can help us to reflect on how much more progress is still needed. Even in its earliest years, photography held out the promise of greater opportunities for representation, but we still have a long way to go to realize the democratizing potential of the medium.

I’ve spent a lot of time studying the period and the history of photography more generally, so of course I love looking at old photographs. Often when looking at portraits from the mid-19th century, you might giggle at a hairstyle or the clothing — but sometimes, if you take the time to look closely at the faces in the pictures, there’ll be an incredible jolt of recognition, some feeling that photographic portraits can transcend time and offer a real sense of empathy. You’ll find yourself staring into a face that looks just like someone you might see on the subway or in line at the grocery store. It forges a remarkable feeling of humanity, of connection.

America has always been a work in progress. Let’s strive to use photographs to help, not hinder, human connectivity.