It’s been said that a man risks his marriage by coming home late—and may put it in even greater jeopardy by coming home early. Though he turns 25 next month, Justin Bieber believes that his late nights and their ruthlessly documented excesses are behind him. In their place, at this moment, the uncounted, uncertain hours of marriage stretch out, a red carpet hung like a tightrope.

It’s just before Christmas, and white, tinseled trees festoon the lobby of the hotel where for years Bieber has lived when he is in Los Angeles. His suite is not quite in keeping with the holiday spirit, piled instead with the giant suitcases that are hardly worth unpacking only to pack again, and there is nothing much to eat, except for potato chips and grapes (simultaneously, as he demonstrates later). Bieber has just returned from an abortive attempt at the Hoffman Process, a weeklong intensive group-therapy retreat with a devoted Hollywood following. He feels that he wasn’t ready. He rushed through the pre-Process questionnaire, and he wasn’t comfortable with the exercises. “There were these séances,” he explains. “Or not really séances but these traditions. They light candles, and it kind of freaked me out. You sit on a mat, you put a pillow down, and you beat your past out of it. I beat the fact that my mom was depressed a lot of my life and my dad has anger issues. Stuff that they passed on that I’m kind of mad they gave me.”

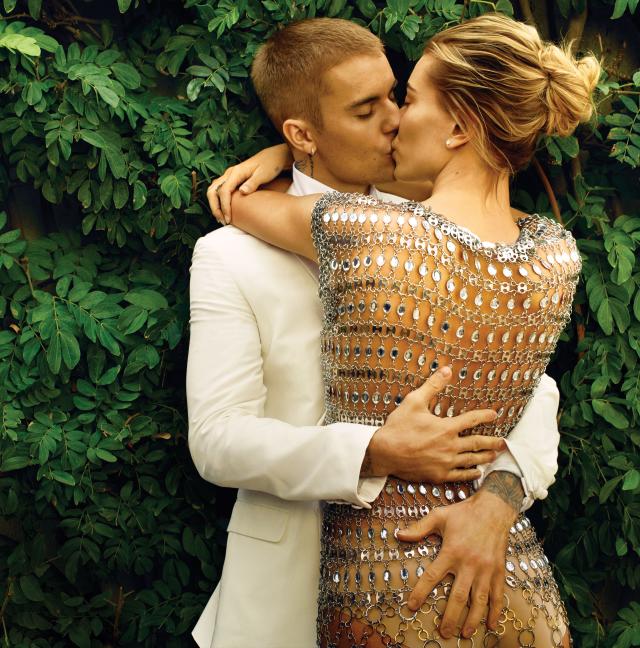

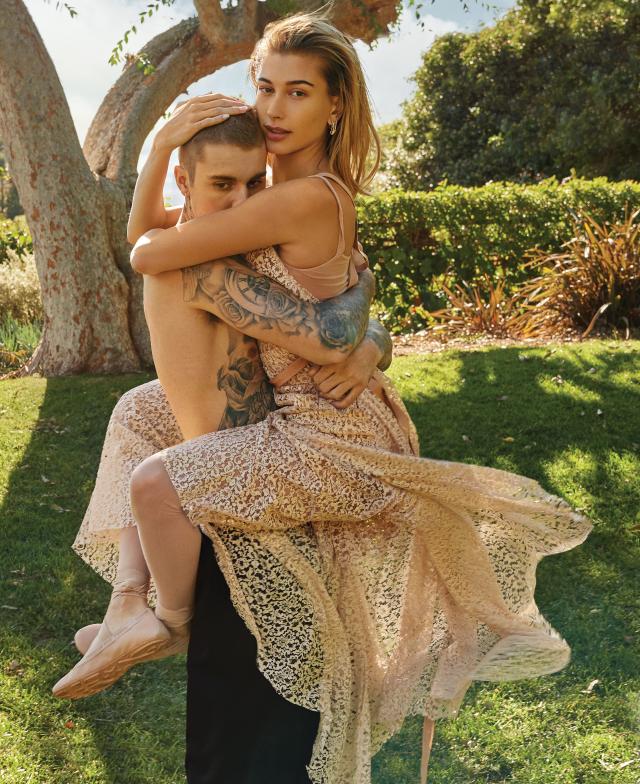

So Bieber left Hoffman’s Napa Valley campus and flew to Seattle, where he joined his wife, the model and TV presenter Hailey Bieber (née Baldwin). They had a meeting with a marriage counselor recommended by their good friend and pastor Judah Smith and then drove to Suncadia, the forest resort where the Smiths have a weekend home. “The thing is, marriage is very hard,” says Hailey. “That is the sentence you should lead with. It’s really effing hard.” The couple, who got married at a lower Manhattan courthouse last September after a twelve-week romance in the context of a nearly ten-year friendship, and who are still finalizing plans for a real wedding, sit side by side on the living room sofa in the oversize and expensive sweat outfits that represent their shared style. But the configuration shifts according to Justin’s restless maneuverings: No sooner has he settled in than he jumps up to do a little jig; he climbs over the sofa, squeezes between Hailey and the bolster and enfolds her in his arms; he spins his body around and puts his head in her lap, then jumps up again, bathes her neck in kisses, and whispers endearments (“Guess what? You’re amazing”) before jolting himself out of his reverie. “It’s hard for me to do just one thing at a time,” he says, his tooth-filled smile like a beacon.

Justin wants me to know that I am catching him at an especially vulnerable moment, and he is nervous. It’s been more than two years since he sat for a lengthy interview, around the release of his fourth (and most recent) studio album, Purpose. At the time he was in the middle of what many were calling an apology tour—a period in which he seemed to be asserting that he had put his now famously bad behavior behind him, coincident with a collection of songs that hit with critics, millennials, and men, not just the teenage girls who had propelled him to a decade of pop hegemony. But after performing more than 150 concerts in 40 countries in sixteen months for Purpose, in the summer of 2017 he canceled the final fourteen shows. “I got really depressed on tour,” he recalls. “I haven’t talked about this, and I’m still processing so much stuff that I haven’t talked about. I was lonely. I needed some time.”

It is impossible not to feel, in Justin’s presence, that he is still recovering from something—the fame whose price was his childhood, the mortification of a thousand magnified adolescent peccadilloes, an accumulated uncertainty about the attentions of those in his orbit—and these scars crowd the surface like his innumerable tattoos. Smith told me that when he first met Justin as a young teenager, he felt called upon to love and protect him. After an hour in his company, I heard some approximation of this call. Journalists have often described Justin as difficult to talk to, a criticism that seems unfair. The frequently interviewed become deft at pivots and obfuscations, and so Justin’s guilelessness can be disarming by comparison. He says just what comes to mind, no filters: “I like you”; “You’re stressing me out, bro.” He produces long, anxious exhalations, he gets the giggles, he apologizes if he’s making me nervous. “It’s been so hard for me to trust people,” he explains. “I’ve struggled with the feeling that people are using me or aren’t really there for me, and that writers are looking to get something out of me and then use it against me. One of the big things for me is trusting myself. I’ve made some bad decisions personally, and in relationships. Those mistakes have affected my confidence in my judgment. It’s been difficult for me even to trust Hailey.” He turns to her. “We’ve been working through stuff. And it’s great, right?”

Justin and Hailey, who is 22, go way back—all the way to a Today-show appearance in 2009 to which she had been given tickets by her uncle the actor Alec Baldwin. Her father, Stephen, and Justin’s mother, Pattie Mallette, who are both born-again Christians, developed a friendship that connected their kids, if not initially with much enthusiasm. Hailey refutes the version of their origin story that casts her as the ultimate Belieber (the name for Justin’s army of fangirls). “I was never a superfan, of him or of anyone,” she says. “It was never that crazed, screaming thing. I didn’t think about it in any kind of way except for the fact that he was cute. Everybody had a crush on him. But for the first few years we had a weird age gap.” They didn’t develop a real friendship until a few years later, when Hailey started attending services at Hillsong, the Australian megachurch whose New York satellite was gathering at Irving Plaza at the time. “One day Justin walked into Hillsong and was like, ‘Hey, you got older.’ I was like, ‘Yeah, what’s up?’ Over time he became my best guy friend. I was running around with him as his homie, but we weren’t hanging out [romantically].”

Justin has been especially focused on his own moral development lately, what he describes as “character stuff.” Last fall he made a decision to step back from music for the moment to focus on being the man he feels no one ever taught him how to be, and above all a good husband. “Just thinking about music stresses me out,” he says. “I’ve been successful since I was thirteen, so I didn’t really have a chance to find who I was apart from what I did. I just needed some time to evaluate myself: who I am, what I want out of my life, my relationships, who I want to be—stuff that when you’re so immersed in the music business you kind of lose sight of.” He has looked to Smith as a role model, just as he turned to the Hillsong pastor Carl Lentz four years ago at what he regards as his personal low point. Justin was raised by a single mother in small-town Ontario public housing, and he burst into fame at age thirteen when the man who would become his manager, Scooter Braun, discovered a group of YouTube videos that his mother had posted. Braun brought him to Atlanta, where he was introduced to Usher and given a new style and a new sound. He worshiped his mentors in hip-hop, absorbing their vernacular, singing about shorties before he knew what the word meant. “I was real at first,” Justin says, “and then I was manufactured as, slowly, they just took more and more control.” It felt fantastic to be famous, to be adored by girls. At sixteen, he blindly believed the hype. “I started really feeling myself too much. People love me, I’m the shit—that’s honestly what I thought. I got very arrogant and cocky. I was wearing sunglasses inside.” (Inside at night, says Hailey.)

By 2013, he had immolated the sugary, prepubescent teen idol. And within another year he was a train wreck. The cringing media cataloged his succession of offenses, from egging a neighbor’s house to urinating in a mop bucket, from turning up in a Brazilian brothel to catching a DUI charge after drag-racing his Lamborghini in Miami Beach. Oh, and there was the unfortunate capuchin monkey seized at customs in Germany. Justin would like to laugh at his teenage self, and indeed he seems torn between self-flagellation and a desire to give himself the break that few others were offering. “A lot of the douchey things I was doing gave people the right to be like, Man, that’s frickin’ douchey, bro. But a lot of the stuff was like—me peeing in a bucket, people made such a big deal of that. Or me owning a monkey. It’s like, if you had the money that I had, why wouldn’t you get a monkey? You would get a monkey!” Internally, Justin was dissolving. He was abusing Xanax, which allowed him to somnambulate through a social life that never squared with his upbringing. “I found myself doing things that I was so ashamed of, being super-promiscuous and stuff, and I think I used Xanax because I was so ashamed. My mom always said to treat women with respect. For me that was always in my head while I was doing it, so I could never enjoy it. Drugs put a screen between me and what I was doing. It got pretty dark. I think there were times when my security was coming in late at night to check my pulse and see if I was still breathing.”

Smith had always been clear that he was there if Justin needed him, but he did not see it as his place to intervene. “I’ve said before that I’ve learned more from Justin than I think he’s learned from me—about the human condition, about pain,” Smith says. “He gives a lot to the world, and a lot has been taken from him, including a bit of the natural progression of development, the chance to grow relationally and socially. He can feel everything, and that’s from those years spent wondering who in the room is being authentic with him. His spider sense is remarkable, but it haunts him a bit. He’ll notice people’s eyebrow movements. I get emotional now, watching him make a great effort to care about the people around him when the last decade of his life was lived in a glass box.”

Lentz has a more tough-love style, and in 2014, as Justin was tanking, he pressed for the singer to move into his home in New Jersey for an informal detox. For several weeks they played basketball, hockey, and soccer. Justin interned for Lentz at Hillsong and refocused on his religious faith. Though he drinks alcohol socially, Justin says that he has not ingested a drug since. Hailey remembers the trip to the Lentzes’ as the culmination of a long, frightening chapter. “I grieved very intensely over the whole situation,” she remembers. “I just wanted him to be happy and be good and be safe and feel joy. But I’m really proud of him. To do it without a program, and to stick with it without a sober coach or AA or classes—I think it’s extraordinary. He is, in ways, a walking miracle.”

Last summer, after years as a nomad, Justin bought a house outside Toronto. The couple settled into it in September, and they agree that real cohabitation—the kind that doesn’t take place in hotel rooms, on vacations—has been a test. They are squabbling over decorating decisions. Healthy communication is a constant challenge, and in therapy they are working on developing an ebb and flow so that their personalities don’t lock horns. Sometimes they tiptoe around each other, and at others they practice arguing without being unkind. “Fighting is good,” Justin says. “Doesn’t the Bible talk about righteous anger? We don’t want to lose each other. We don’t want to say the wrong thing, and so we’ve been struggling with not expressing our emotions, which has been driving me absolutely crazy because I just need to express myself, and it’s been really difficult to get her to say what she feels.”

“You’ll get it out of me the next morning,” Hailey promises. She admits that the first weeks of marriage were deeply lonely for her. She felt homesick for her parents, even though she hadn’t lived with them in five years. Perhaps hardest of all was her sense that in marrying Justin she suddenly had a hundred million rivals. So many people on social media seemed to be rooting for them to fail. No one appreciated how seriously she had taken the decision to get married, how much she had prayed about it. “I prayed to feel peace about the decision, and that’s where I landed,” she explains. “I love him very much. I have loved him for a long time.”

When the couple reconnected last June, Justin was more than a year into a self-imposed tenure of celibacy. He had what he calls “a legitimate problem with 𝑠e𝑥.” It was his remaining vice, an addiction that had long since ceased to provide him any pleasure. Not having 𝑠e𝑥, he decided, was a way for him to feel closer to God. “He doesn’t ask us not to have 𝑠e𝑥 for him because he wants rules and stuff,” Justin explains. “He’s like, I’m trying to protect you from hurt and pain. I think 𝑠e𝑥 can cause a lot of pain. Sometimes people have 𝑠e𝑥 because they don’t feel good enough. Because they lack self-worth. Women do that, and guys do that. I wanted to rededicate myself to God in that way because I really felt it was better for the condition of my soul. And I believe that God blessed me with Hailey as a result. There are perks. You get rewarded for good behavior.” People have speculated that Justin and Hailey married because she got pregnant, which is false. (No babies for at least a couple of years, Hailey says.) Justin admits that while a desire finally to have 𝑠e𝑥 was one reason they sped to the courthouse, it was not the only reason. “When I saw her last June, I just forgot how much I loved her and how much I missed her and how much of a positive impact she made on my life. I was like, Holy cow, this is what I’ve been looking for.”

One thing they have learned is that they are pretty happy homebodies. They like to lounge around the house, watch movies, listen to music and dance in their kitchen. Though there is work to do, Justin wishes that Hailey would take just a little pressure off herself. “She’s trying to be this grown-up,” he says. “I think we can be married and still have fun and enjoy our adolescence. That’s something we’re talking about.”

“It’s just that I’m fighting to do this the right way, to build a healthy relationship,” Hailey clarifies. “I want people to know that. We’re coming from a really genuine place. But we’re two young people who are learning as we go. I’m not going to sit here and lie and say it’s all a magical fantasy. It’s always going to be hard. It’s a choice. You don’t feel it every single day. You don’t wake up every day saying, ‘I’m absolutely so in love and you are perfect.’ That’s not what being married is. But there’s something beautiful about it anyway—about wanting to fight for something, commit to building with someone. We’re really young, and that’s a scary aspect. We’re going to change a lot. But we’re committed to growing together and supporting each other in those changes. That’s how I look at it. At the end of the day, too, he’s my best friend. I never get sick of him.”

Justin grins. “And you’re my baby boo.”