In 1914, Rakhaldas Banerji, Director of the Western Archaeological District in Bombay (now Mumbai), went to investigate a series of mounds near the town of Dokri in Sindh Province, Pakistan. The site had never been excavated as locals believed the site to be cursed and that anyone who climbed the mounds would turn blue! Previous investigations revealed the remains of a stupa dating to the 2 nd century BC, but Banerji believed that buried beneath the mounds were the ruins of a much older city.

Banerji obtained permission to undertake excavations of the mounds, and investigations soon confirmed his suspicions. Jewelry, weights, finely painted pottery, and numerous square seals depicting strange writing and engravings of animals and people, similar to those already found at Harappa, began to emerge from the earth. Could it be that the objects were made by people of the same culture as those at Harappa, some 680 kilometers (420 miles) away? The possibility was tantalizing!

Large-scale excavations were launched, led by the Director General of the Archaeological Survey of India, Sir John Marshall, and it was not long before explorations revealed the immense, and very ancient city of Mohenjo Daro. Its name means ‘Mound of the Dead Men’, as it was a city that had been dead, buried, and forgotten for thousands of years.

Mohenjo Daro Emerges from the Dust

The almost simultaneous discovery of ancient cities at Mohenjo Daro and Harappa gave the first clue to the existence around 5,000 years ago of a civilization in the Indus Valley to rival those known in Egypt and Mesopotamia. It is now known that the Indus Valley civilization, or Harappan civilization as it is sometimes called, emerged at least as early as 3,000BC and flourished for 1,200 years.

Its cities demonstrated an exceptional level of civic planning and amenities. The houses were built with kiln-fired bricks and were furnished with bathrooms, many of which had toilets. Wastewater from these was led into well-built brick sewers that ran along the centre of the streets, covered with bricks or stone slabs. Cisterns and wells finely constructed of wedge-shaped bricks held public supplies of drinking water.

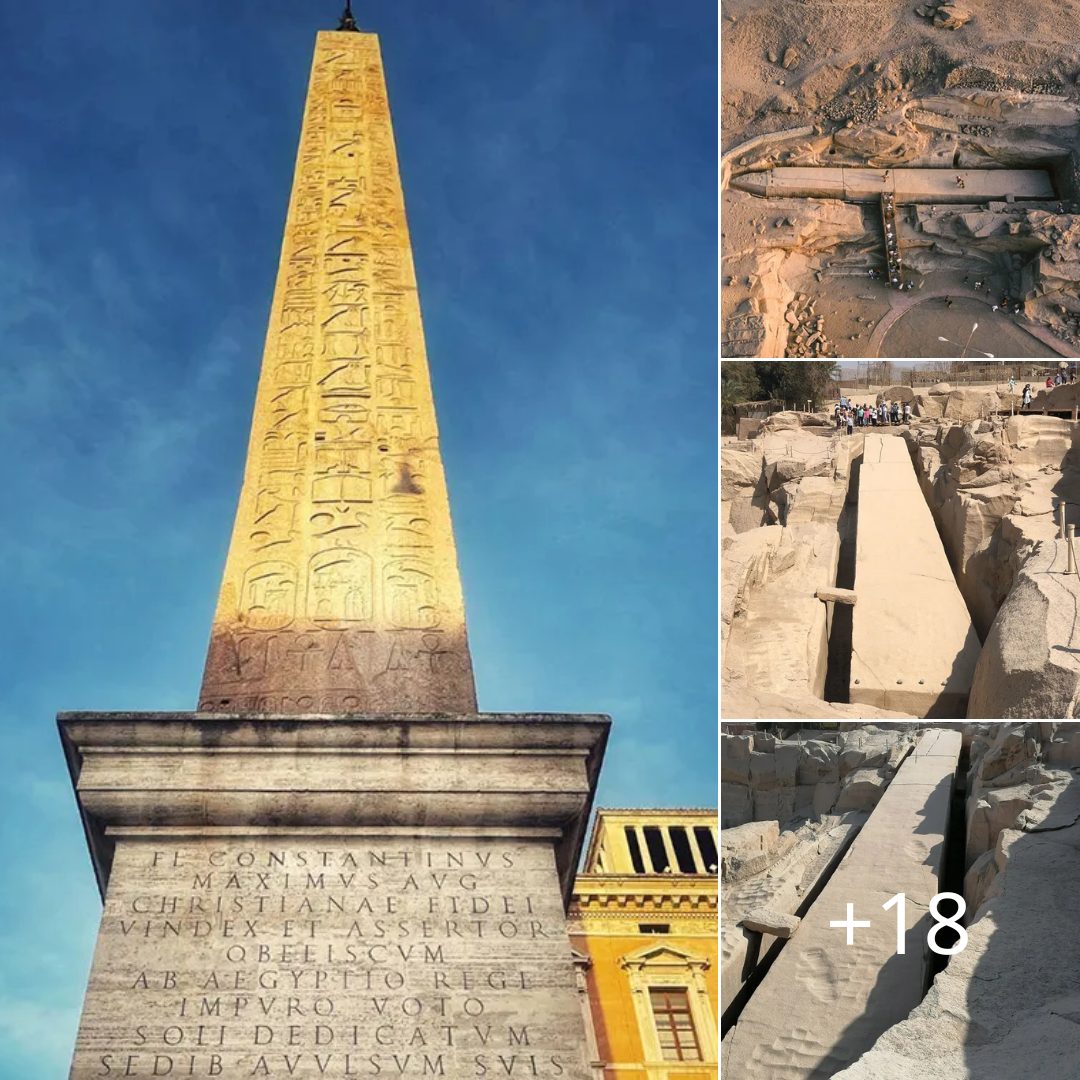

Mohenjo Daro was spread over an immense area of over 100,000 m2 (1,076,390 ft2) containing over 300 dwellings. It also boasted a Great Bath on the high mound known as the citadel, which overlooks the residential area of the city. Built of layers of carefully fitted bricks, gypsum mortar and waterproof bitumen, the bath even had change rooms and a hot-air heating system.

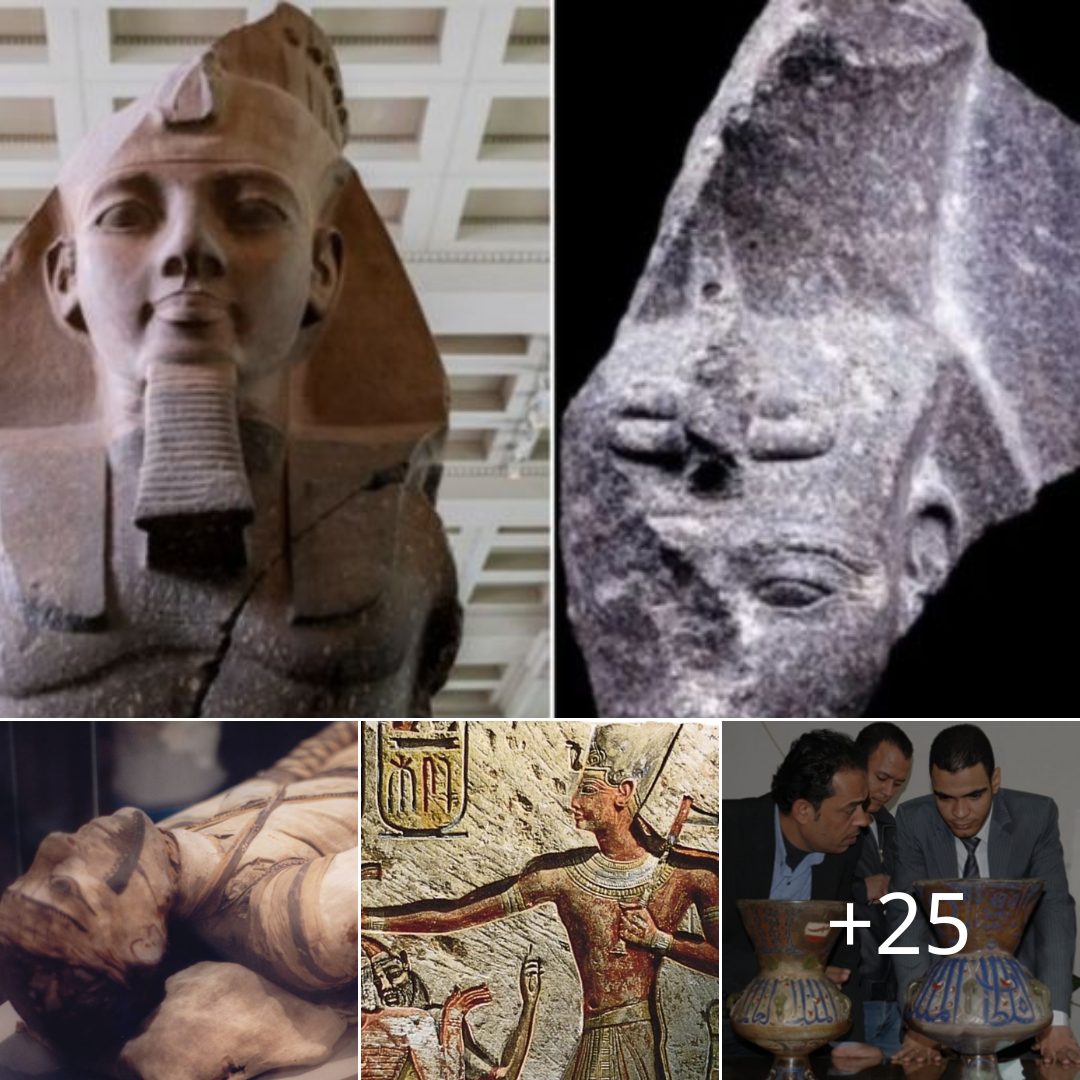

More than 40,000 artifacts recovered from the excavations have helped researchers piece together the lives of the Mohenjodarans. They include a celebrated bronze statue of a semi-naked dancing girl, perfectly shaped clay urns, platters, ovens and stone weights and measures. A set of carved seals hints at a revenue collection system, while hand-carved figures such as chess pieces and clay toy animals reveal the city’s more playful side.

The Great Bath at Mohenjo Daro. Source: Nilkishore / Adobe Stock

The Mystery of the Forty-Four

Around 1800 BC things changed for the Indus Valley civilization. Archaeological records indicate that cities began falling into disrepair, and settlements were being abandoned. Standardized weights used for trade purposes appeared to fall out of use and evidence of writing started to disappear. By around 1500 BC, the civilization had all but collapsed. What happened to bring this immense civilization to an end?

Perhaps Mohenjo Daro could offer some clues.

In the uppermost levels at Mohenjo Daro, amidst the intermingling of residential and industrial buildings, archaeologists under the direction of Sir John Marshall, unearthed several dozen sprawled skeletons, or parts thereof, lying scattered in streets and houses. The remains of 37 men, women, and children were found in total, while later excavations unearthed more, bringing the total to 44. Excavation reports described them as lying in layers of rubble and debris or in the streets in contorted positions that suggested violent death.

Archaeologist Harold Hargreaves, who was responsible for excavations in the 1920s in the southernmost excavation area of the city, wrote in an excavation report that the discovery of the skeletons “appear to indicate some tragedy”, and the positioning of their bodies are those “likely to be assumed in the agony of death”. Archaeologist Ernest Mackey, who conducted excavations at the site from 1926 to 1931 concurred, suggesting that they had been slaughtered by raiders while attempting to escape from the city.

Sir Mortimer Wheeler, the last Director of Archaeology in India who excavated at Mohenjo Daro in the 1950s, maintained they were all victims of a single massacre and suggested that the Indus civilization, whose demise was unexplained, had fallen to an armed invasion by Indo-Aryans, nomadic newcomers from the northwest, who are thought to have settled in India during the second millennium BC. Wheeler claimed the remains belonged to individuals who were defending the city in its final hours. He was so convincing that this theory became the accepted version of the fate of Mohenjo Daro.

Skeletal remains at Mohenjo Daro ( George Dales )

However, for the massacre theory to hold up as a valid explanation for the scattered skeletal remains of the forty-four, Dr George Dales, one of the last archaeologists to excavate the site, points out that we need a lot more than the odd and haphazard positioning of the remains: “Where are the burned fortresses, the arrowheads, weapons, pieces of armor, the smashed chariots and bodies of the invaders and defenders?”, he asks in his paper The Mythical Massacre at Mohenjo Daro. The answer is that despite extensive excavations at Mohenjo Daro, none were ever found.

“There is no destruction level covering the latest period of the city, no sign of extensive burning, no bodies of warriors clad in armor and surrounded by the weapons of war,” writes Dr Dales. “The citadel, the only fortified part of the city, yielded no evidence of a final defence.”

Further evidence unravelling the massacre theory came in the form of more precise dating assigned to different layers of ruins at Mohenjo Daro, as well as to the skeletons themselves. One investigation, for example, examined the remains found in a street known as ‘Deadman’s Lane’. Parts of a skeleton were scattered, positioned diagonally across what was once a narrow lane, giving the impression that the individual had been killed in the street and left there. However, archaeologist Dr Dales reports that dating revealed the lane belonged to the Intermediate Period of the Indus Valley civilization (approximately 2600 BC to 1700 BC), but the skeleton was not lying directly on the surface of the lane and appears to have fallen through debris from a house rebuilt over the lane in the Late Period (1700 to 1300 BC).

It is now believed there could be up to 1,000 years in between the time that some of the individuals died, meaning there was no single tragedy that killed the forty-four, and in fact, they may all have died very uneventful and natural deaths.

Archaeologists estimate that at its peak, Mohenjo Daro was home to some 40,000 people. So why only forty-four bodies? To date, no cemetery has ever been found in Mohenjo Daro or its surrounds. If such a site is ever found, it may offer the key to answering many of the questions that still remain about this impressive civilization.

The citadel at Mohenjo Daro. Source: Aleksandar / Adobe Stock

The Downfall

So what did bring about the final demise of Mohenjo Daro, and indeed the civilization as a whole?

We may never know with certainty, but a number of factors appear to have played a significant part in its downfall. The Indus River was prone to change its course and through the centuries moved gradually eastward, leading periodically to flooding within the bounds of the city. Indeed, the massive brick platforms on which the city is constructed and the fortifications around parts of it seemed to have been designed to provide protection against such floods. However, investigations revealed considerable evidence of flooding at Mohenjo Daro in the form of many layers of silty clay. Conditions would have been ideal for the spread of water-borne diseases, especially cholera, although cholera epidemics cannot be proved to have occurred.

Around the same time, Mesopotamia, their main trading partner, was going through immense political turmoil and this may have caused trade networks to collapse, which would have had a massive impact across the Indus Valley region.

The mystery of the forty-four may have been solved but continuing archaeological and anthropological work is needed across India and Pakistan to unravel the last secrets of this enigmatic civilization.

Clay bricks from the Indus Valley civilization with images and script. Source: Haider Azim / Adobe Stock

Mohenjo Daro Under Threat

Although it has survived for five millennia, Mohenjo Daro now faces imminent destruction. While the intense heat of the Indus Valley, monsoon rains, and salt from the underground water table are having damaging effects on the treasured site, it is the visitors that flock in their thousands to the site that are the biggest threat. Adding to the problem is a lack of funding, public indifference, and government neglect. The government even approved a festival being held at the site back in 2014, where tents, lights and stages where hammered into the walls of the delicate ruins.

Mohenjo Daro is already in an incredibly fragile condition. It is estimated that at its current rate of degradation, the World Heritage listed site could be gone within 20 years . Experts are now saying that the only way to save it is to rebury the city. The loss of Mohenjo Daro would not only be a great national tragedy for Pakistan, it would be a loss to the entire world.