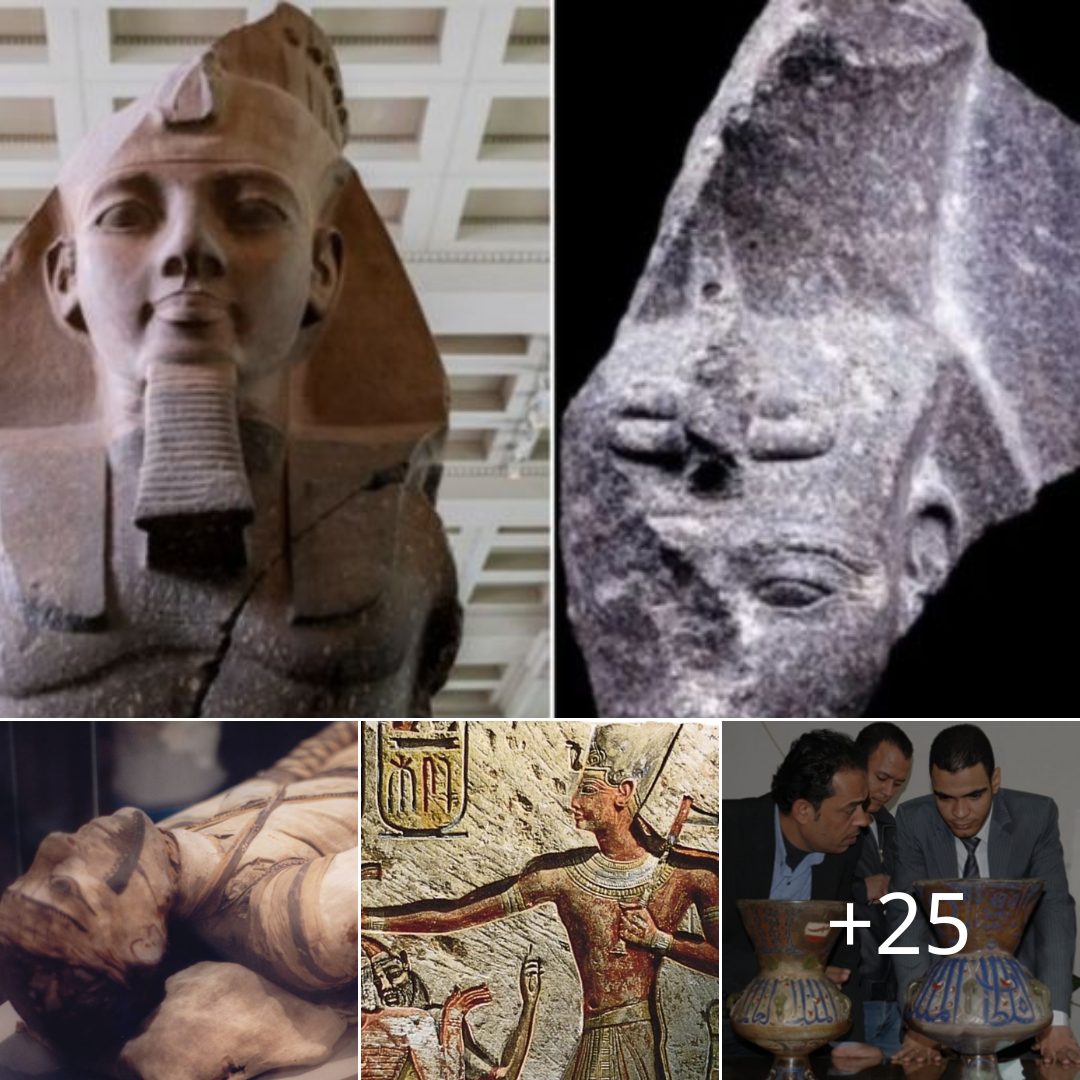

Nuestras imágenes exclusivas muestran a científicos coreanos de la Universidad Nacional de Seúl trabajando en restos humanos en el Centro Científico de Investigación del Ártico. Foto: Sergey Slépchenko

Las últimas pruebas realizadas a los restos momificados de este niño medieval del norte de Siberia ponen de relieve el gran conocimiento que puede aportarnos sobre su forma de vivir. Cuando tenía seis o siete años, lo encerraron en corteza de abedul y cobre y lo encontraron en una antigua necrópolis cerca del actual sitio de Salekhard, en el Círculo Polar Ártico.

Nuestras imágenes exclusivas muestran a científicos coreanos de la Universidad Nacional de Seúl, encabezados por el destacado experto internacional Profesor Dong Hoon Shin, trabajando en restos humanos en el Centro Científico de Investigación del Ártico.

El experto ruso Dr. Sergey Slepchenko, de Tyumen, dijo: “Lo principal es que esta momia se conservó de forma natural y los órganos internos no fueron extraídos, a diferencia de las momias artificiales”.

“Lo principal es que esta momia se conservó de forma natural y los órganos internos no fueron extraídos, a diferencia de las momias artificiales”. Imágenes: Sergey Slepchenko, Vesti.Yamal

Tissue samples will reveal a mass of information about how this 800 year old boy once lived. Tests include histological analysis on the mummy’s tissue and its changes.

Study is also being made on histochemical and biochemical features and the research on stable isotopes.

‘All this will help us to learn as much as possible about the preservation status of Zeleny-Yar-mummies in general, and the lifestyle of this child – how he lived, what he ate,’ he said. ‘If we are lucky, we have a slight chance of a hint on how he died. The odds are not great, but we hope.’

Samples were also taken from previously undisclosed partially mummified bodies found at the same Zeleny Yar in the past year. ‘For example, this year were found the remains of a young man with a mummified pelvis.

‘The upper part of his body is badly preserved, but the pelvis is mummified, so we could take the samples from his bowel and bladder. That is – our main goal is to restore the picture of life of these people, to learn as much as possible about them.’

A myriad of other research is being conducted on this mummy, highlighting its importance to new revelations about life in the pre-historic Arctic. Hopes remain in scientific efforts to discover the DNA of the mummy, although the process is taking longer than expected.

Already, local native groups from northern Siberian are having their DNA analysed in the hope of an ‘Are you my mummy?’ matching, as previously disclosed by The Siberian Times.

For example, local Nenets journalist Khabecha Yaungad is seen here giving a blood sample for genetic analysis. As he describes his family’s past, there is an intriguing example of where the stories derived from oral history may meet scientific scrutiny.

Local Nenets journalist Khabecha Yaungad is seen here giving a blood sample for genetic analysis. Pictures: Vesti.Yamal

‘My forefather arrived here 700 years ago, and he was drowning in the river, but then he was washed up on a log, and my great-grandmother healed him,’ he said, reaching back into the stories he had heard from his family’s past.

‘And then he married her daughter. They began to think, which family name to give him? And the decided: ‘There are thousands of shells on the riverbank. Let us call him Shell.’ In the Nenets language, his family name means ‘shell’.

South Korean scientists are also working on elaborate research to recreate the face of this medieval child. ‘The degree of preservation is very good, so we think that the reconstruction will be successful,’ said Dr Slepchenko.

Other work is underway to create a 3D model of the mummy. Mikhail Vavulin, of the Artefakt Laboratory at Tomsk State University, said: ‘Currently scientists from Salekhard are developing a plan for the mummy’s conservation and restoration, so it was very important to make a scan before they start this work.’

Temple rings and a bronze axe, found at the burial site, were also scanned.

Alexander Gusev, investigador del Centro para el estudio del Ártico, que dirigió la expedición para desenterrar la momia, dijo: “En Zeleny se probaron nuevas oportunidades en la creación de modelos de sitios arqueológicos con ayuda de escaneo tridimensional Yar por primera vez en 2013-2014.

Estos modelos digitales permiten observar el entierro desde cualquier ángulo. “Cualquier investigador puede ver con todos los detalles y desde todos los ángulos lo que los científicos vieron durante las excavaciones en el sitio arqueológico”, dijo. Los restos del niño se consideran conservados accidentalmente gracias a la forma de entierro en un capullo de abedul. corteza y cobre. Foto: Alexander Gusev

Otros hallazgos nuevos son que el niño estaba cubierto de “piel” de reno cuando fue enterrado para la posteridad. “La capa superior era la piel de un reno, la capa inferior era la ‘pelo’ del mismo animal”, dijo Gusev.

«Es difícil decir cuál era originalmente la capa inferior: tal vez la piel de un cervatillo o la piel especialmente procesada de un reno adulto. “Estamos trabajando en esto”, dijo. “Además, estaban las pieles de zorro y zorro ártico”.

Se considera que los restos del niño se conservaron accidentalmente gracias a la forma de entierro en un capullo de corteza de abedul y cobre. Nuestras historias anteriores muestran cómo su rostro, incluidos sus dientes, se hizo repentinamente visible por primera vez en unos ocho siglos.