The rich historical tapestry of Greece has been dramatically expanded with the recent discovery of hunting tools dating back an astonishing 700,000 years. Unearthed in a coal mine in Megalopolis, these ancient stone tools have not only pushed back Greece’s historical timeline by a staggering quarter of a million years but have also opened a window into the development of our ancient hominin ancestors before their migration to northern Europe.

Megalopolis: Where Time Began

The ancient Greek city of Megalopolis was located in Arcadia, a region in the central Peloponnese peninsula of Greece. The original settlement was founded in 371 BC by the Theban general Epaminondas, during the Peloponnesian War, to counter the power of Sparta and to support the independence of the smaller Greek city-states.

Megalopolis shares the same sun-battered landscapes as Olympia, Mycenae and Pylos, each of which feature centrally in Greek mythology. Olympia, the home of the Olympic Games, housed the chief sacred site of the god Zeus, and Mycenae was the city of the legendary King Agamemnon who led the Greeks during the Trojan War. Pylos, was a centre of the Mycenaean civilization most famously ruled by King Nestor, and it featured in Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey.

But now, the recent discovery of very ancient stone tools in a coal mine are shadowing the nation’s semi-mythological history, by revealing valuable secrets about the development of our ancient hominin ancestors, before they populated northern Europe.

A Game Changing Discovery

According to a report in Greek City Times the latest archaeological discoveries in Megalopolis are “game-changing.” In the oldest-known archaeological site in Greece, dating back approximately 700,000 years, not only did the archaeologists recover the remains of now extinct giant deer, elephants, hippopotamus, rhinoceros, and a macaque monkey, but they also found stone tools from the Lower Palaeolithic period (3.3 million to 300,000 years old).

The skull of a member of the deer family in Megalopolis (Greek Culture Ministry)

Used for butchering animals and chopping plants approximately 700,000 years ago, the still sharp stone flakes are suspected to have been manufactured by a Lower Palaeolithic Homo antecessor, considered a possible ancestor of both Neanderthals and modern humans. While this is yet to be confirmed, if hominin remains are discovered, the find pushes back Greece’s official archaeological record by up to 250,000 years.

Until now, the oldest tools in Greece date back to around 500,000 years ago, and were discovered in the Petralona Cave, in the Chalkidiki region of northern Greece. These stone tools were unearthed alongside the fossilized remains of an ancient human skull, known as the Petralona Skull, and such a discovery would need to be made at the Megalopolis site to definitely date the new discoveries.

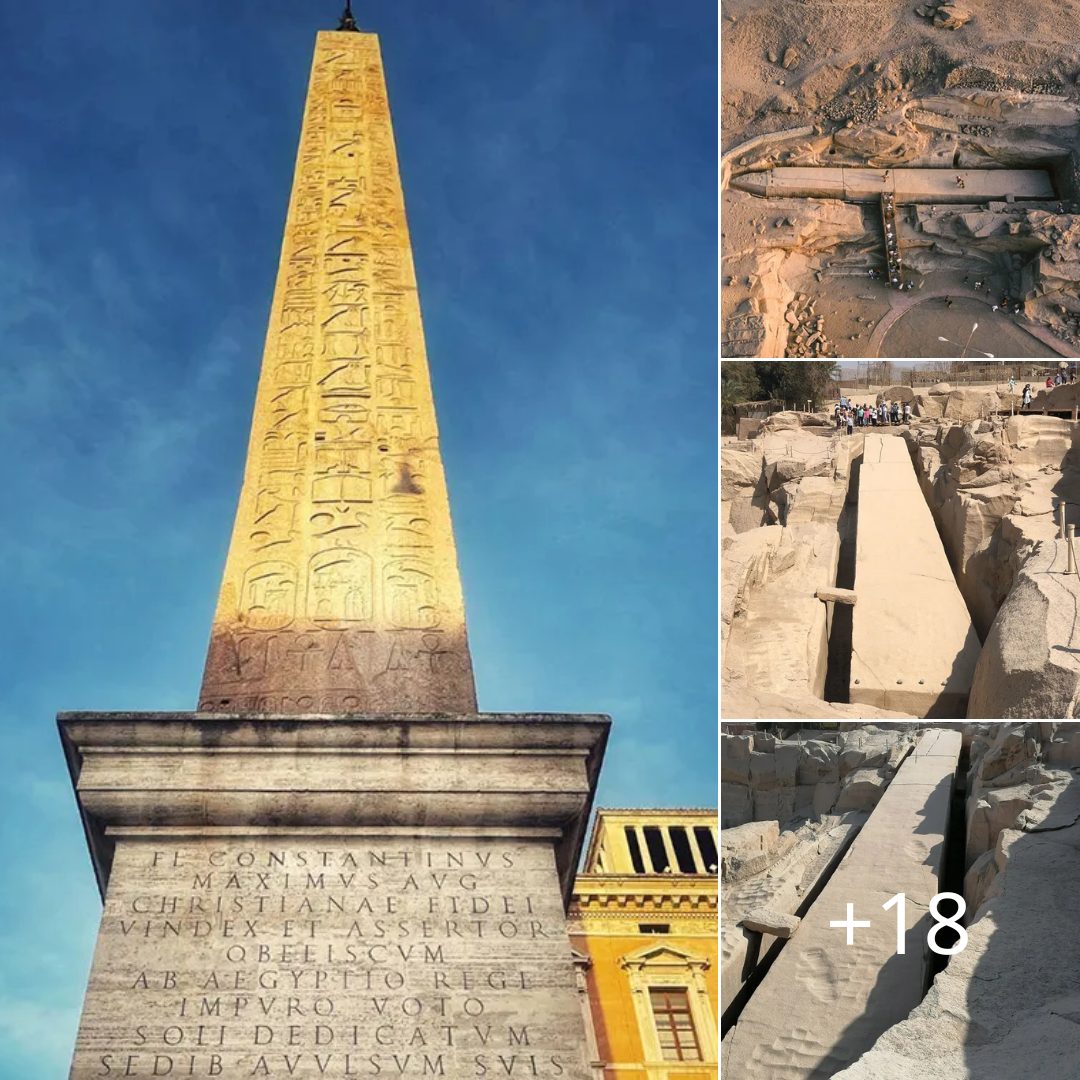

Stone tools dating back 700,000 found in the coal mine. (Greek Culture Ministry)

Pushing Back Archaeological Timelines

These new finds come after a 5-year-long project led by Professor Panagiotis Karkanas of the American School of Classical Studies in Athens, Eleni Panagopoulou from the Greek Ministry of Culture and Katerina Harvati, a professor of paleoanthropology at the University of Tübingen in Germany.

An article in Breaking News said these “groundbreaking discoveries surpass any previously known archaeological record in Greece.” And, if the dating is confirmed, what these finds demand, effectively, is a rewriting of Greek archaeology with a new starting point at around 700,000 years ago.

A Second Stunning Discovery

In addition to this main discovery, the team of archaeologists explored a second site in the Megalopolis area where they found “the oldest Middle Palaeolithic remains ever found in Greece, dating back approximately 280,000 years.” In conclusion, the researchers said of this second discovery, that it suggests Greece played a significant role in stone industry developments throughout ancient Europe, “solidifying its position as a pivotal hub of ancient civilisation.” Furthermore, the researchers said this discovery further illustrates what is known about “hominin migrations to Europe and human evolution as a whole.”

Megalopolis declined in importance following the rise of Macedon under Philip II and his son, Alexander the Great, and it finally lost its prominence during the Roman era, after which it faded into obscurity. Today, the ancient ruins of Megalopolis can still be visited, but these new archaeological discoveries extend well beyond the ancient city’s history and architecture, providing new insights into Greece’s ancient past.