The salve predates the peak of mummification in the region by some 2,500 years.

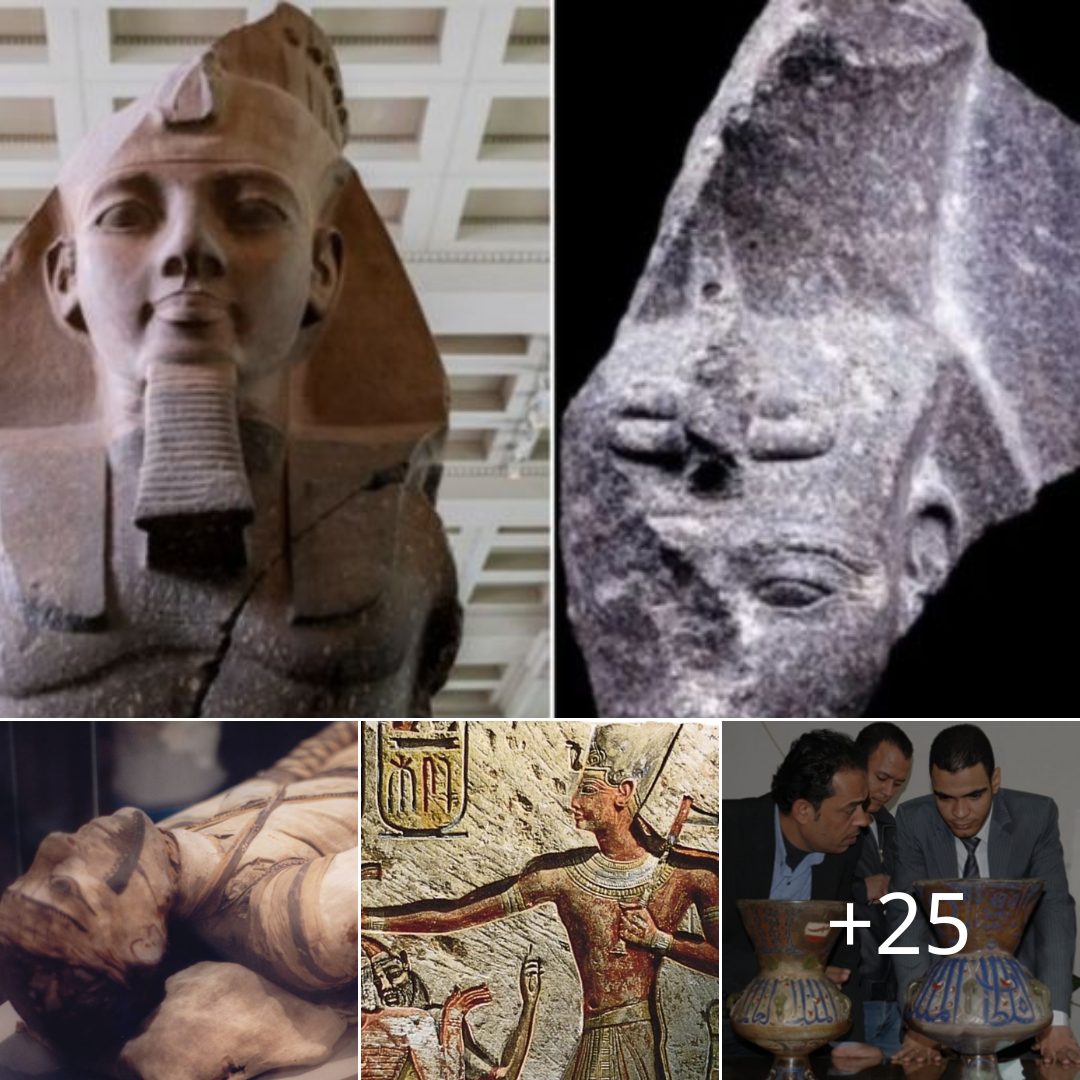

The mummy lays delicately curled in the fetal position. Though it now rests in a museum in Turin, Italy, it assumed its vulnerable pose thousands of years ago in Egypt, baked in the searing sands near the banks of the Nile.

Dating to some 5,600 years ago, the prehistoric mummy at first seemed to have been created by chance, roasted to a decay-resistant crisp in the desert. But new evidence suggests that the Turin mummy was no accident—and now researchers have assembled a detailed recipe for its embalmment.

5:58

The Ancient Egyptian civilization, famous for its pyramids, pharaohs, mummies, and tombs, flourished for thousands of years. But what was its lasting impact? Learn how Ancient Egypt contributed to society with its many cultural developments, particularly in language…

The ingredient list represents the earliest known Egyptian embalming salve, predating the peak mummification in the region by some 2,500 years. But this early recipe is remarkably similar to the later embalming salves used in extensive rituals to help nobles like King Tut pass into the afterlife.

“It’s really interesting to see those connections,” says Stuart Tyson Smith, an archaeologist from the University of California, Santa Barbara, who was not part of the study team. “It gives us a nice piece of the puzzle that we didn’t have before.”

“An Incredible Feeling”

The study, published today in the Journal of Archaeological Science, comes after decades of meticulous work with prehistoric mummies. Study coauthor Jana Jones, an Egyptologist at Macquarie University, got her first hints of this early mummification in the 1990s, when she was studying ancient mummy wrappings that date to roughly 6,600 years ago.

Jones peered at the wrappings under a microscope and was astounded: The cloths appeared to contain remnants of an embalming resin, a compound commonly seen in later mummies. “It was just an incredible feeling,” she says.

But microscopic evidence wasn’t enough to say Egyptians embalmed their dead thousands of years earlier than previously thought. That required careful chemistry, and it took Jones and her team 10 years to complete the analysis. “That was just the curse of the mummy,” she quips. The team finally confirmed the find on the wrappings in 2014, publishing those results in PLOS ONE.

“That was the ground-breaking moment,” says Stephen Buckley, an archaeological chemist and expert in mummification who led the chemical analysis for both the 2014 study and this latest work.

But some experts remained skeptical, Jones says. The researchers lacked evidence from an actual mummy, since the textiles had long been separated from their preserved owner. So they turned to the Turin mummy for more clues.

Nail in the Sarcophagus

The Turin mummy—or “Fred” as he is often affectionately called—has been housed in Turin’s Egyptian Museum since the early 1900s, and he had remained untouched by modern preservatives and unstudied by scientists.

The researchers subjected samples from the mummy to a battery of tests, teasing out the precise chemical components of the ancient embalming recipe. They found that the salve had a base of plant oils that was then mixed with plant gum or sugars, heated conifer resin, and aromatic plant extracts. The latter pair of ingredients are particularly important, since they stave off microbial growth.

The components of the paste not only resemble those used thousands of years later in Egypt, but they also bear a striking similarity to the chemistry of the salve researchers had identified in the prehistoric mummy wrappings.

“It’s confirming our previous research, undoubtedly,” says Jones.

Ancient Egypt’s most famous pharaoh was the offspring of a union between siblings. Inbreeding may have afflicted him with a congenital clubfoot and even prevented him from producing an heir with his wife, who was probably his half sister.</p>

Ancient Egypt’s most famous pharaoh was the offspring of a union between siblings. Inbreeding may have afflicted him with a congenital clubfoot and even prevented him from producing an heir with his wife, who was probably his half sister.

PHOTOGRAPH BY KENNETH GARRETT, NAT GEO IMAGE COLLECTION

With their commonly curled positions and organs still inside their shriveled bodies, prehistoric mummies are a far cry from the classic entombed mummies that come to mind when you think of Egypt. But the basic idea behind an embalming salve remained the same.

The balm would have formed “sort of a sticky brown paste,” Jones says. Bandages were either dipped before wrapping, or the embalmer would directly smear the paste on the body. The mummy was then positioned in the hot sand so that a combination of the searing sun and balm preservatives would keep the body safe.

Later “classic” mummies were more often laid flat and interred in tombs far from the sun’s rays. Because of this, Buckley says, the embalmers had to take additional measures, such as removing the brain and other organs, as well as desiccating the body with a type of salt called natron.

Recipe Reconstruction

The study also suggests that early embalming practices were much more widely spread than once thought. The wrappings analyzed in the earlier study hail from a part of Egypt that’s over a hundred miles north of where the Turin mummy was likely preserved.

So how did ancient Egyptians figure out the recipe so long ago?

“Some of these ingredients may well have had a symbolic significance initially,” Buckley speculates. “But then they noticed that they had a preservative benefit.” The team is now studying sites of early experimentation with embalming ingredients, says Buckley, hinting at a future publication.

Ronn Wade, retired director of the anatomical services division of the University Maryland, praised the new study for its thoroughness. In 1994, Wade replicated the Egyptian mummification process on a modern human with support from a National Geographic grant.

“I wish we had some of this information when we were doing our mummy,” he says. “That would have been interesting.”

5:58

5:58